Articles

How Plants Live:

Water Absorption

Author: Fidelia Sihombing | Publication Date: 16 January 2026

Water is the most important compound for plants, comprising 80% to 95% of the weight of actively growing tissues and herbaceous structures, such as leaves and flowers. Water not only fills the plant body but also influences every plant activity, as life itself cannot exist without it.

Water is crucial for plants for several important functions:

- Structural Support. Water is a hydraulic agent that maintains turgor pressure within plant cells. Turgor pressure keeps cells in a swollen and rigid (turgid) state, allowing the plant to stand upright and support its physical structure. Plants lacking water will lose turgidity and wilt.

- Photosynthesis and Metabolism. Water is the primary reactant in the process of photosynthesis. Plants use sunlight to combine water and carbon dioxide, producing glucose (an energy source). Water is also a universal solvent for biochemical reactions and a reagent in many plant physiological processes.

- Internal Transport System. Water enables the movement of nutrients and minerals absorbed from the soil through the roots and into the xylem vessels. Water, along with the phloem, transports sugars (products of photosynthesis) and hormones from the leaves to various parts of the plant.

- Temperature Regulation. Plants cool themselves by releasing water through leaf pores (stomata).

- Growth and Development. Water allows for cell expansion during growth and development. Water absorption (imbibition) is a crucial first step in activating enzymes and initiating the germination process.

Undeniably, water is an essential component required by plants for survival and growth. So, how does water move from the soil to the roots, and then throughout the plant’s body?

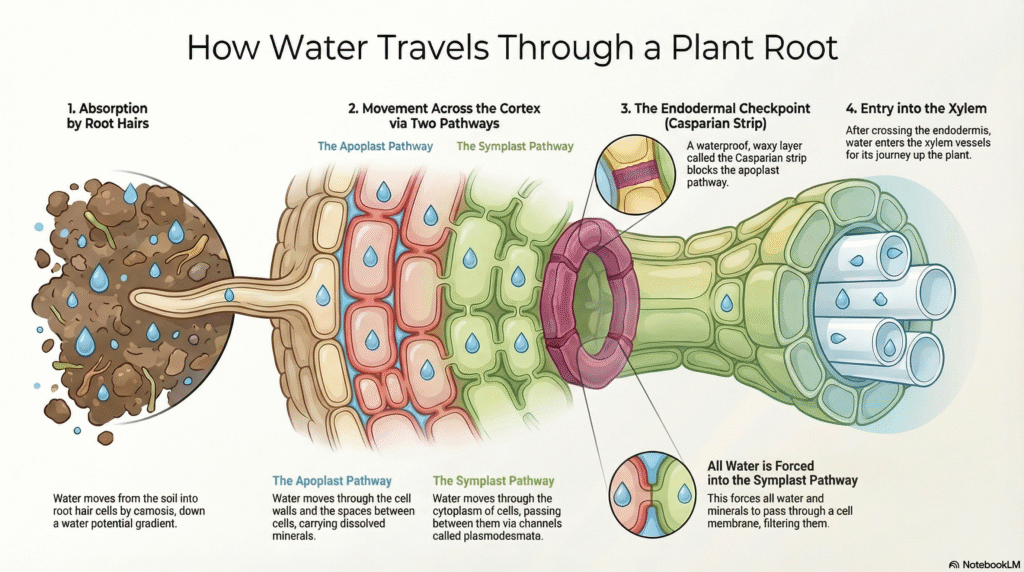

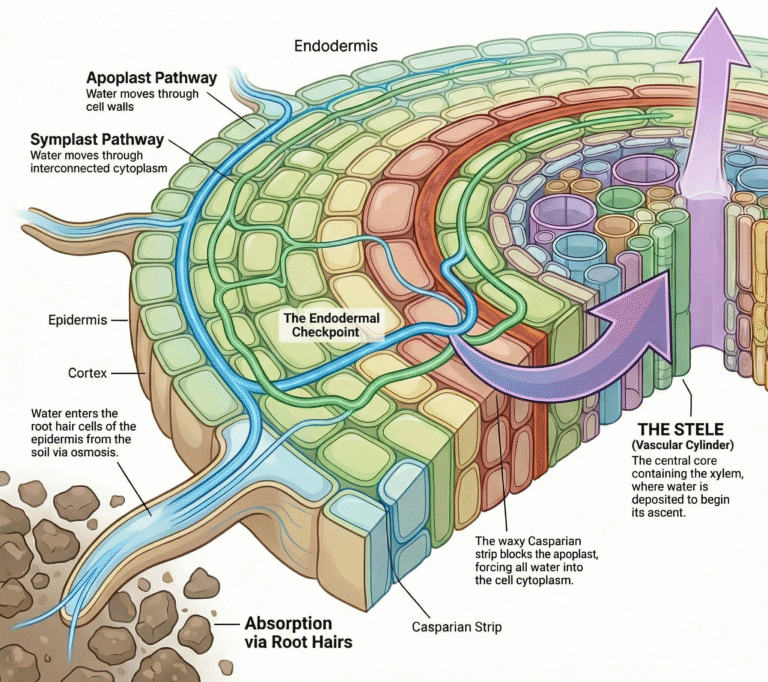

Figure 1. How water travels through a plant root (image generated by NotebookLM)

Root Structure and Water Absorption Zone

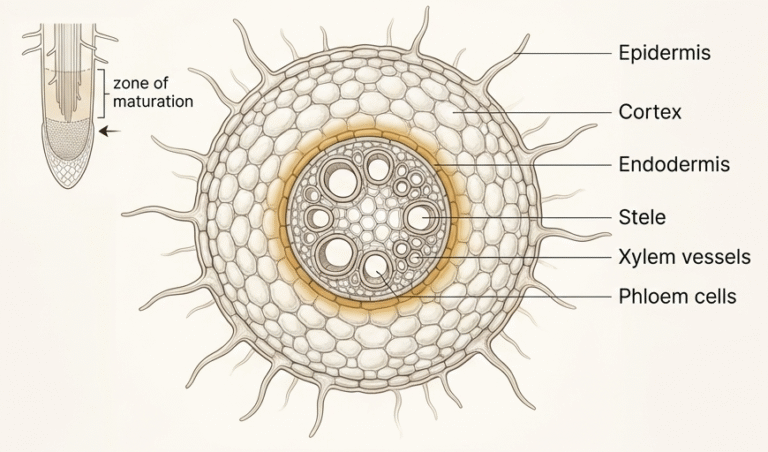

Figure 2. Root anatomy (image generated by NotebookLM)

From the outermost to the innermost, roots consist of distinct layers.

- Epidermis (Hairy Layer). The outermost layer of the root. In the zone of maturation, epidermal cells produce root hairs. Root hairs are single, tube-shaped cells that grow through the small spaces between soil particles until they reach the water droplets. These hairs increase the surface area for water osmosis. Root hairs have a thin, waxy cuticle and a hydrophilic wall layer composed of cellulose and pectin, allowing for unimpeded water flow.

- Cortex. A thick layer composed of parenchyma cells, through which cells must pass to reach the center. Water travels through the cortex via the apoplast (cell wall), symplast (cytoplasm), or transmembrane.

- Endodermis. The innermost barrier of the cortex. Contains the Casparian strip, a water-repellent band composed of suberin wax. This strip blocks the apoplast pathway, forcing water and minerals into the cytoplasm, allowing water molecules to filter before entering the root hair core.

- Stele (Vascular Cylinder). This is the main core of the root, consisting of the pericycle and vascular tissue.

- Xylem: a tube-like tissue composed of dead cells that functions to transport water and dissolved minerals to the upper part of the plant.

- Phloem: a living tissue that transports sugars and photosynthetic products from the leaves to the root tip and other storage organs.

Entry: Root Hairs

Most water is absorbed in the root hair zone at the epidermal layer, near the tip of the root. Root hairs are single, tube-shaped cells that grow into the tiny spaces between soil particles, via osmosis.

Figure 3. Root hairs

Absorption Mechanisms

Plants use two modes to draw water into their root systems:

- Passive Absorption. This is the dominant mechanism in plants that transpire. This absorption occurs because transpiration causes tension that is transmitted through the xylem to the roots. The roots act as passive conduits, and the absorption rate is directly proportional to the transpiration rate.

- Active Absorption. This absorption occurs when the transpiration rate is low, for example, at night. The roots utilize energy (ATP) to generate the force necessary for collecting minerals in the xylem. This causes the osmotic potential to decrease, drawing water into the vascular tube and generating root pressure that pulls water upward.

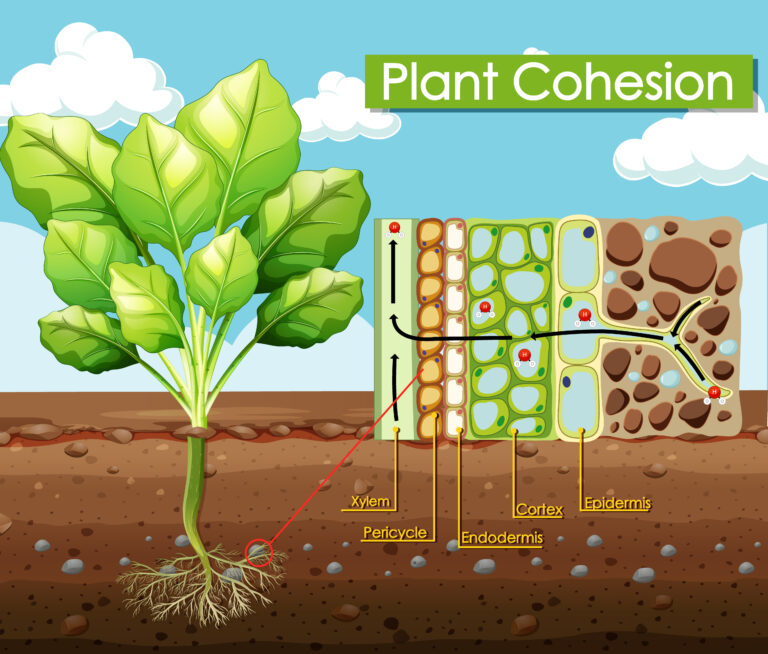

Figure 4. Plant cohesion

Water Journey Through Roots

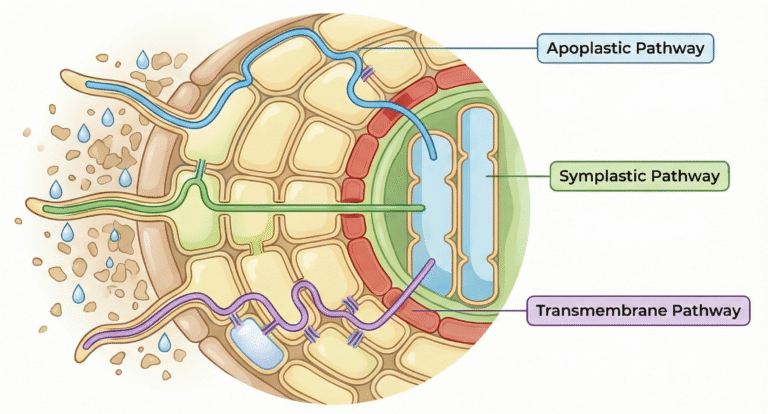

Once water has entered the root hairs, it must travel through the cortex to reach the central vascular tissue (stele). There are three routes of water journey through root:

- Apoplast. Water moves rapidly through the non-living parts of the plant, primarily the cell walls and intercellular spaces. This route is fast and has little resistance, but is not selective.

- Symplast. Water enters the protoplasm and moves from one cell to the next through plasmodesmata channels. The Casparian strip plays a role in directing water to enter the symplastic route. This route is slower because water passes through the plasma membrane, allowing the plant to absorb certain ions.

- Transmembrane. Water crosses the plasma membrane and cell walls of each cell layer individually. This movement is often facilitated by aquaporins, specialized proteins that regulate membrane permeability and act as water channels.

Figure 5. Water Radial Pathway (image generated by NotebookLM)

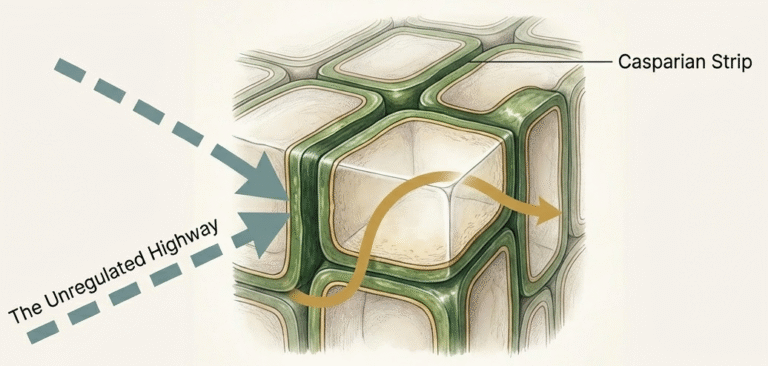

The Casparian Strip: Water Pathway Guide

The Casparian strip is a specialized band composed of suberin (a water-resistant, waxy polymer) located in the radial and transverse walls of endodermal cells. Its primary function is to direct water flow by acting as an absolute barrier to the apoplast.

- Transition to the Symplastic Pathway. Since the Casparian strip is impermeable, it blocks the movement of the apoplast through the cell wall. This allows water and minerals to enter the living cytoplasm (symplast) of endodermal cells through the selectively permeable plasma membrane.

- Filtration and Regulation. The transition to the symplastic pathway also allows the selection and filtration of solutes, the concentration of essential nutrients, and the prevention of toxic substances or pathogens from entering the primary transport stream.

- Induces Root Pressure. As a result of its presence, the Casparian strip helps maintain the osmotic pressure necessary to generate root pressure, which can “push” water upwards when transpiration rates are low.

Figure 6. Casparian Strip (image generated by NotebookLM)

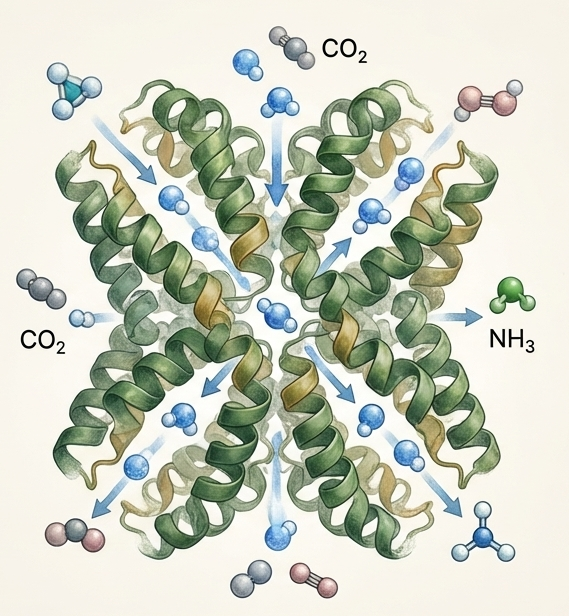

Aquaporins: The Molecular Gateways of Plant Hydraulics

Aquaporins are special proteins in cell membranes that form channels to help water move quickly and in a controlled way across membranes.

Aquaporins play a central role in water uptake and distribution through several key mechanisms:

- Facilitating the Transmembrane Pathway. Although water can move through both the apoplastic and symplastic pathways, aquaporins are the primary facilitators of the transmembrane (transcellular) pathway, where water must pass through the lipid layer. This pathway is highly regulated, as plants can adjust their permeability by altering the activity of aquaporins.

- Gatekeepers in Root Tissues. Aquaporins are often concentrated in “gatekeeper” cell layers, such as the endodermis and epidermis. They provide a low-resistance pathway for water to enter the vascular cylinder (stele) and ultimately the xylem vessels for vertical transport.

- Maintaining Turgor and Cell Growth. Aquaporins help maintain turgor pressure by facilitating the rapid entry of water into cells. This is essential for cell expansion and structural rigidity.

- Regulating Root Hydraulic Conductivity. Aquaporins enable plants to adjust their water supply to transpiration needs. Their expression often increases during the day when transpiration is high and decreases at night or under stress.

Figure 7. Aquaporins (image generated by NotebookLM)

Entering the Stele

Water that has passed through the endodermis and Casparian strip checkpoints arrives at the stele (the central vascular cylinder of the root). Several processes occur that allow air to be transported to the upper part of the plant.

- Entering the Pericycle. Water travels to the pericycle, the outermost layer of the vascular tube. The pericycle serves as the final transit point before water enters the vessels.

- Loading into the Xylem. Water and minerals are released into the xylem vessels and tracheids. Because mature xylem cells are dead and hollow, they are considered part of the apoplastic pathway. Solutions that have been filtered into this space by the living cells of the stele and endodermis.

- Formation of Root Pressure. Minerals are often actively transported from parenchyma cells into the xylem. The accumulation of these solutes lowers the water potential within the vascular tube, drawing more water through osmosis. This process generates root pressure, a hydrostatic force that helps move water upward through the stem, especially when transpiration rates are low.

- Vertical Bulk Flow. After entering the xylem, water forms a continuous column held in place by cohesion and adhesion. The air then moves en masse upward through the roots and stems to reach the leaves. At any point during this upward journey, air can also move laterally out of the xylem to meet the metabolic needs of other surrounding tissues.

Figure 8. Water Entering Stele (image generated by NotebookLM)

Why Plant Water Relations Matter

Water absorption is more than a physiological process; it is the foundation of both plant and human life. Every water molecule that enters a plant supports not only the plant’s structure and metabolism, but also the ecosystem and a vital food source for humans. Without efficient water absorption and regulation, plants cannot grow, reproduce, or survive environmental stresses.

Global climate change intensifies droughts, alters rainfall patterns, and increases temperature extremes, making the regulation of water by plants crucial. The water absorption mechanisms described in this article, from root hairs and Casparian strips to aquaporin gatekeepers, are not merely academic concepts. Plant survival during droughts, forests’ resistance to degradation, and land productivity depend on them.

At PEFORDEI Research, we see the plant-water relationship as a crucial link between fundamental biology and real-world solutions. Insights into water absorption help develop climate-resilient crops, guide sustainable land management practices, and deepen our understanding of plant adaptation to environmental stress. By studying how plants move, regulate, and conserve water, we will gain tools to support agriculture, maintain ecosystems, and ensure food and nutritional security for a growing global population.

Figure 9. PEFORDEI Research Logo

Conclusion

Water is the lifeblood of plants. From the moment it enters through root hairs, to its movement through specialized pathways and plant membranes; it maintains structure, sustains metabolism, and supports growth. Plants’ ability to regulate the amount of water they absorb, through barriers like the Casparian strip and regulatory proteins called aquaporins, demonstrates a system shaped by millions of years of evolution.

Understanding how plants absorb and regulate water reminds us that plants are not passive organisms. They actively regulate their internal processes, respond to changing environments, and maintain balance under stress conditions. With climate change intensifying, knowledge about plants is more than just information; it is crucial.

Plant science allows us to see hidden processes and translate them into beneficial actions. By learning how plants live, we can take a step forward in creating a food-secure future.

Reference

- 4.5.1.4: Water Absorption. (2020, May 29). Biology LibreTexts. https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Botany/Botany_(Ha_Morrow_and_Algiers)/04%3A_Plant_Physiology_and_Regulation/4.05%3A_Transport/4.5.01%3A_Water_Transport/4.5.1.04%3A_Water_Absorption

- Chaumont, F., & Tyerman, S. D. (2014). Aquaporins: Highly Regulated Channels Controlling Plant Water Relations. Plant Physiology, 164(4), 1600–1618. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.233791

- Fanourakis, D., Heuvelink, E., & Carvalho, S. M. P. (2013). A comprehensive analysis of the physiological and anatomical components involved in higher water loss rates after leaf development at high humidity. Journal of Plant Physiology, 170(10), 890–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2013.01.013

- How Plants Absorb Water | RHS Advice. (2025, December 19). https://www.rhs.org.uk/advice/understanding-plants/how-plants-absorb-water

- Taiz, L., Møller, I. M., Murphy, A., & Zeiger, E. (Eds.). (2023). Plant physiology and development (Seventh edition). Oxford University Press.

Let’s Advance Plant Science Together

From research collaborations to training and consultation, we’re here to connect knowledge with impact. Join us in exploring the hidden power of plants for health and sustainability..